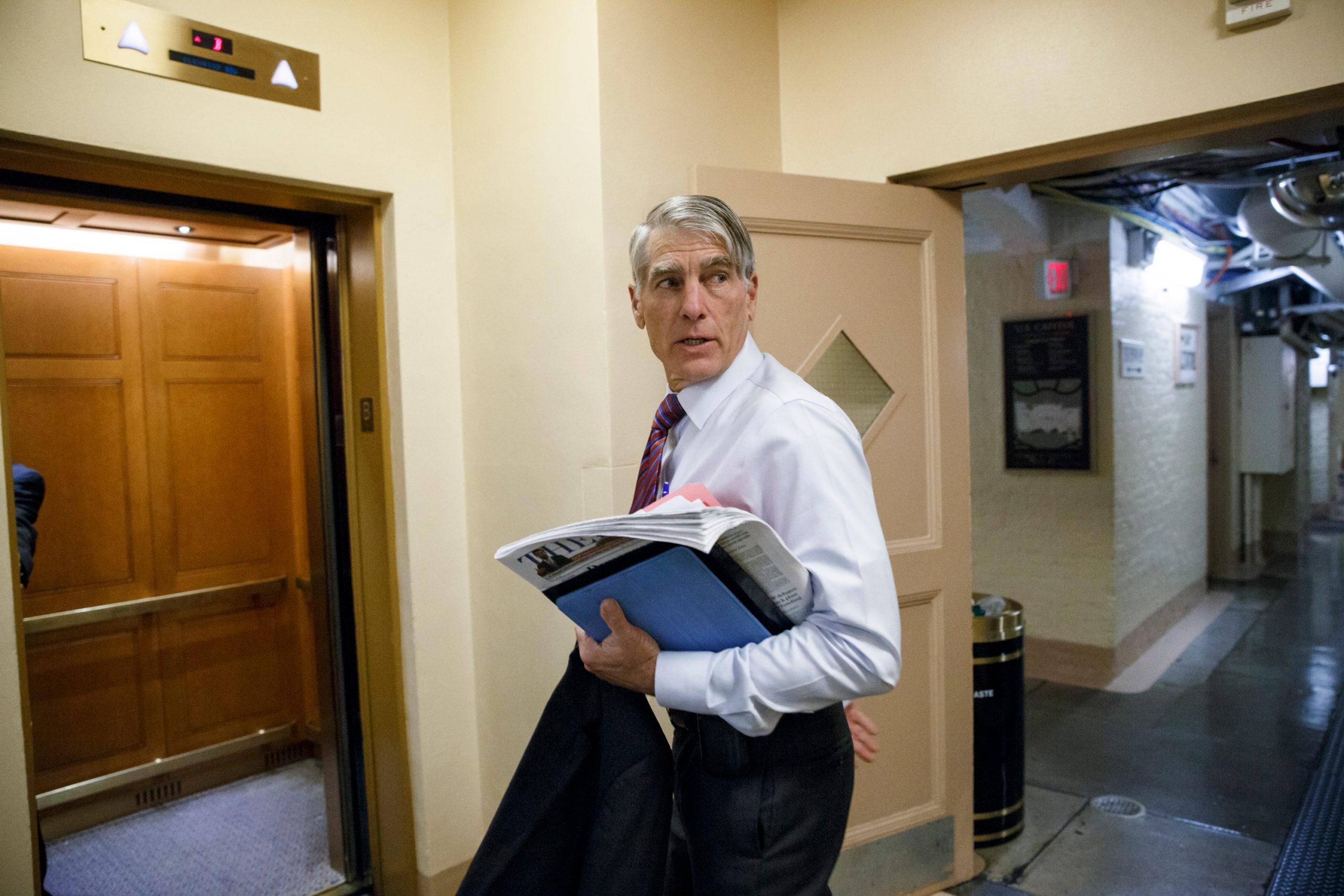

Former Colorado Sen. Mark Udall is still haunted by the interrogation techniques the CIA used on terror suspects after 9/11.

The controversy over those methods, and the battle to make them public, are the subjects of a new movie called “The Report,” now playing in theaters and streaming on Amazon Prime. Udall is played by Scott Shepherd.

Udall, a Democrat, served in the U.S. Senate from 2009-2015. He was a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, which investigated the CIA’s program for more than five years. The committee released a 500-page summary of its work in December 2014. A day later, Udall took to the Senate floor and made a blistering speech.

“The CIA has lied to its overseers and the public, destroyed and tried to hold back evidence, spied on the Senate, made false charges against our staff and lied about torture and the results of torture and no one has been held to account,” he said.

One detainee died of hypothermia after being chained to the floor of his cell and doused repeatedly with water. Others were subjected to mock burials, days without sleep and repeated waterboarding, all aimed at getting them to provide intelligence about potential terrorism.

“We crossed the line,” Udall said.

The CIA’s methods were called enhanced interrogation techniques but Udall said that was, “a euphemism for terror.”

“It’s the considered opinon of many that we were acting unconstitutionally, illegally, immorally and we were putting our military personnel at risk because of the Geneva Convention’s prohibitions on torture,” he said.

The CIA’s practices “still haunt me,” Udall said.

“Waterboarding … I’m at a loss for words describing it. But we’ve all had our experiences as individuals where you can’t breathe, you feel so desperate and so out of control,” he said.

The interrogation program began under President George W. Bush because CIA officials were embarrassed by the agency’s failure to prevent 9/11 and worried that the FBI and military were outpacing them in the race to gather intelligence after the attacks, Udall said. So, they went to the White House and got legal approval to use the controversial techniques.

Traditionally, interrogators try to build trust with detainees to get them to provide information. But the CIA contracted with two psychologists who touted a different plan. They argued that methods like waterboarding would frighten the detainees into submission. The film questions the psychologists’ credentials and points to their lack of experience in interrogation or in dealing with terror suspects.

The Senate Intelligence Committee began its investigation after a New York Times report described the CIA’s methods.

“The Senate has an important role to play in overseeing all of the actions and activities of the executive branch, especially in the realm of intelligence gathering, given the abuses historically that have occurred,” Udall said.

Then-presidential candidate Barack Obama called the CIA’s activities torture during his campaign and ended them shortly after he took office. But he and his administration also spent years trying to block the release of the committee’s 6,000-page report. They argued, among other things, that the interrogations produced intelligence that led to a courier for Osama bin Laden and, ultimately, to Bin Laden’s capture and death.

In a statement when the report was released, then-CIA director John Brennan defended the interrogation methods, saying they produced “intelligence that helped thwart attack plans, capture terrorists, and save lives … The intelligence gained from the program was critical to our understanding of al-Qa’ida and continues to inform our counterterrorism efforts to this day.”

But Udall said the interrogations never produced actionable intelligence, and the movie argues that the leads to Osama came from a variety of other sources and intelligence methods.

In the end, after extended negotiations with the Obama administration, the committee released the 500-page summary of its report. Udall says he was satisfied with that at the time, but now believes the full report should have been released.

“The whole report would serve us well in reminding ourselves that never again should we undertake the use of torture,” he said.