Grand Junction housing advocates are coalescing around a new, city-backed initiative to help unhoused residents that may not have happened if not for a surprise decision to close a city park that roiled local activists.

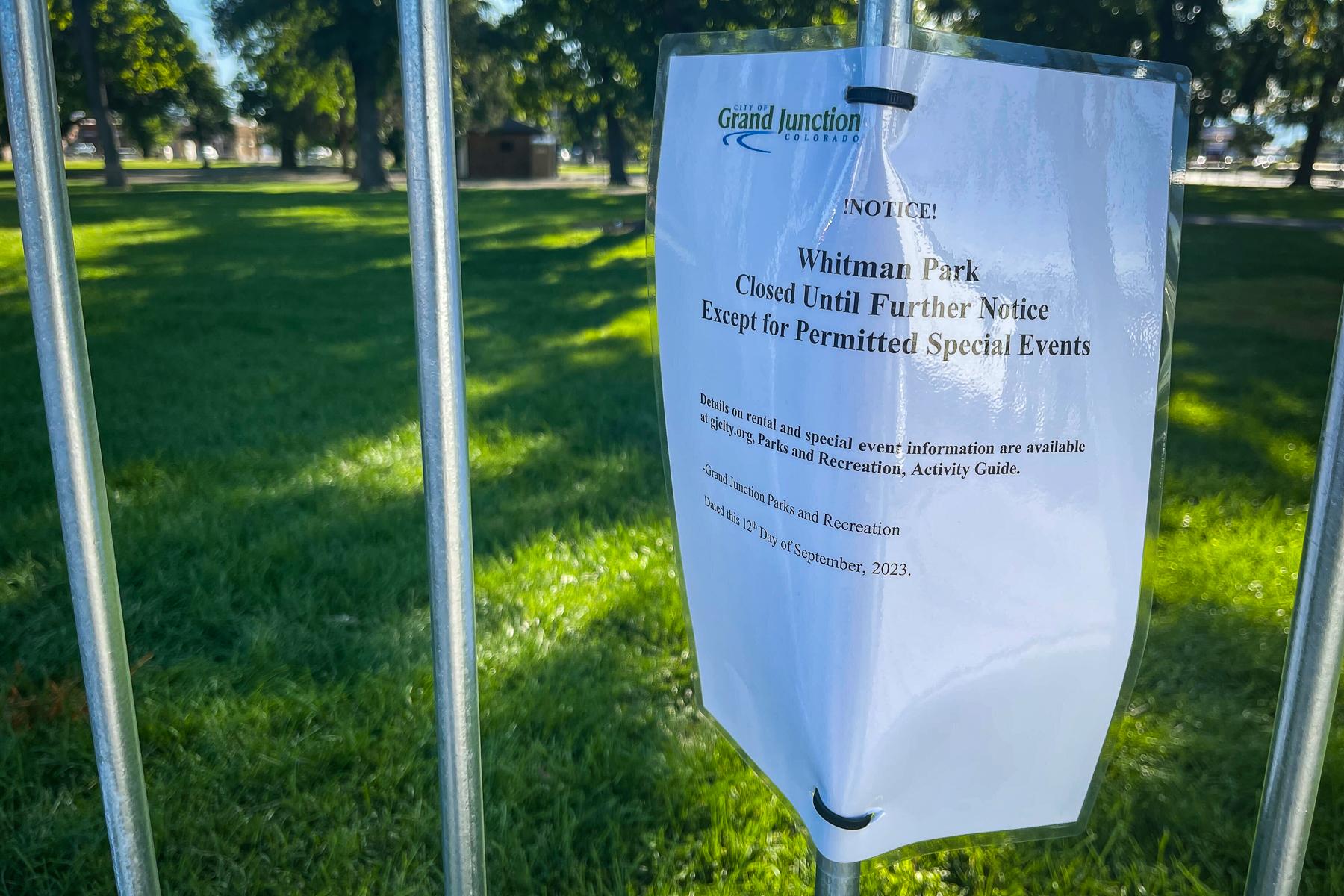

A resource center for those experiencing homelessness is set to open almost exactly three months after $26,000 worth of steel barricades went up around Whitman Park, a downtown space frequented during the day by Grand Junction’s homeless community. The resource center will offer day space, services and amenities like showers and bathrooms.

Stephania Vasconez, executive director for Mutual Aid Partners, said Grand Junction nonprofits felt like the park closure was sprung on them. Whitman Park had long been an unofficial hub for locating and helping unhoused residents. But, closing it forced those groups to come up with something more official.

“That completely catalyzed speeding this up,” Vasconez said. Her organization, Mutual Aid Partners, will be among the groups offering services to residents at the new pavilion, which will be located about two blocks west of Whitman Park and have a “low barrier to entry” intended to make it easier for people to use. The hope, Vasconez added, is that the resource center will offer the same community, safety and basic amenities that Whitman Park was being used for but without some of the violence and neighborhood concerns that factored into the park getting shut down in September.

“What I think is really great is that we just start out with centering the voices of people experiencing homelessness. And what they've told us is they want accessibility to basic needs that include restroom facilities, that include handwashing stations, showers, laundry, that they want a place where they don't feel stigmatized, where they can just be and have some stability.”

— Stephania Vasconez, executive director for Mutual Aid Partners

Threading the needle

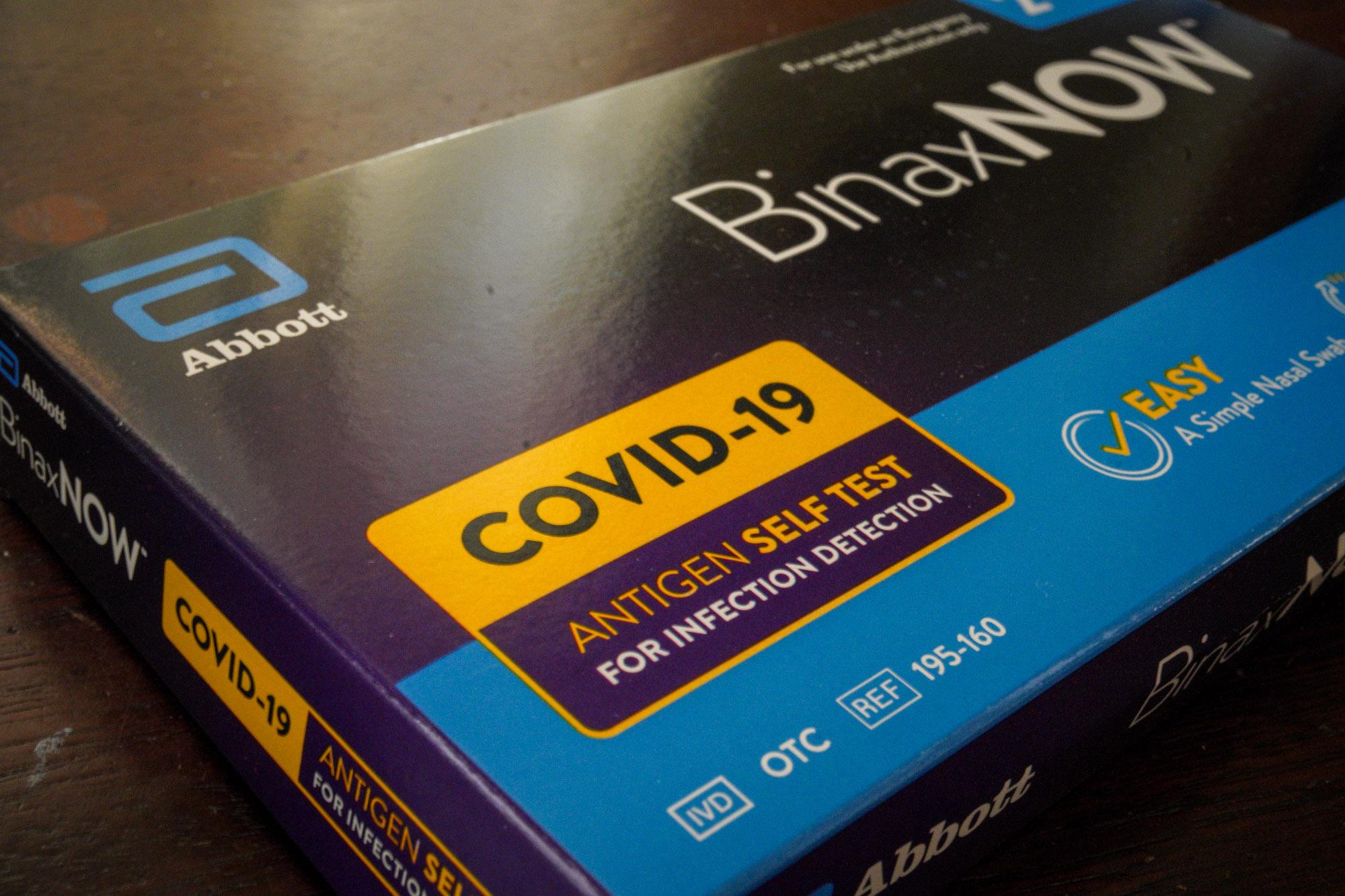

The center will be set up on city property, feature a hard-sided pavilion that can be heated and cooled, and is being paid for with about $900,000 of federal COVID-19 relief dollars allocated by the city. HomewardBound, a housing nonprofit, and the United Way of Mesa County will help staff the center.

“When Whitman Park closed, one of the biggest things that the houseless population lost was their community center, the place where they met their friends, where they managed relationships,” Rick Smith, executive director of HomewardBound said. “All of that occurred when they congregated in Whitman Park. When it closed, they lost that. They lost that entire relationship. So one of the most important things we wanted to provide with this resource center was a place for them to regain that.”

That loss of a gathering place was mentioned repeatedly in the weeks following the closure of Whitman Park, when local organizers and former members of the unhoused community took city officials to task for the way the move was handled. When the park was closed, city leaders spoke primarily about plans to revive the park, make it available for reservations for special events and protect its historic tree canopy. It was only in the weeks following that city leaders discussed violence.

Now, Grand Junction Mayor Anna Stout says the city is seeking to address those concerns over community with a balance for individual well-being.

“This is something that we as a community and we as a city specifically think is really important that if you're in a vulnerable situation like homelessness, that you're not also then being sort of relegated to places where you are not safe,” Stout said. “We've had multiple incidents in our parks, and specifically at Whitman Park where people have been victims of crime.”

Open to suggestions

Smith, with HomewardBound, said the resource center is also intended to be a learning opportunity. The plan is that they can refine their offerings based on what they hear from the people who use it. That same concept helped shape the conversations around creating the center in the first place. An unhoused needs assessment commissioned by the city was among the factors in identifying what type of space was wanted.

The intention is for the resource center — which is meant only for day use — to be a temporary project, operating for a few years, according to Stout.

In that time, Smith’s goal is to create a hub that would begin lifting members in this community out of homelessness.

“We hope that this will evolve into an environment where houseless people can access medical care, can access mental health services, and can access our assistance and community navigation,” he said.

Vasconez is meeting with resource providers, city officials and business leaders who have been the most vocally frustrated by unhoused gathering spaces. She said organizers are considering everything from how to manage pets at the resource center to incorporating Mesa County Public Health and figuring out employment or community service projects to engage residents who want it.

“We've already had folks asking if there's going to be a possibility for jobs, on-site day things. So we're talking to the Workforce Center about what does that look like. We're talking to the library about different programming that could potentially help with education and GEDs … I'm very, very optimistic,” Vasconez said.

In recent months, Grand Junction has committed more resources to housing services. Stout says no single approach will solve the problem, but is confident in the direction the city is taking. In November, the nonprofit Catholic Outreach broke ground on a new facility to house at-risk individuals. That project, which is directly across the street from Whitman Park, came with significant city backing. Another service provider that focuses on resources for women and children, is doing an expansion project backed by more than $900,000 in city funds.

Vasconez thinks the resource center, which is estimated to open in mid-December, has the potential to be a key factor in the community’s answer to its unhoused crisis. Its low barrier to entry should make it easier for residents to use and hopefully benefit from it. If the catalyzing force that inspired the resource center in the first place persists, Vasconez said the impact could be profound.

“I really feel like it's limitless,” she said, “as long as everybody gives it a chance.”